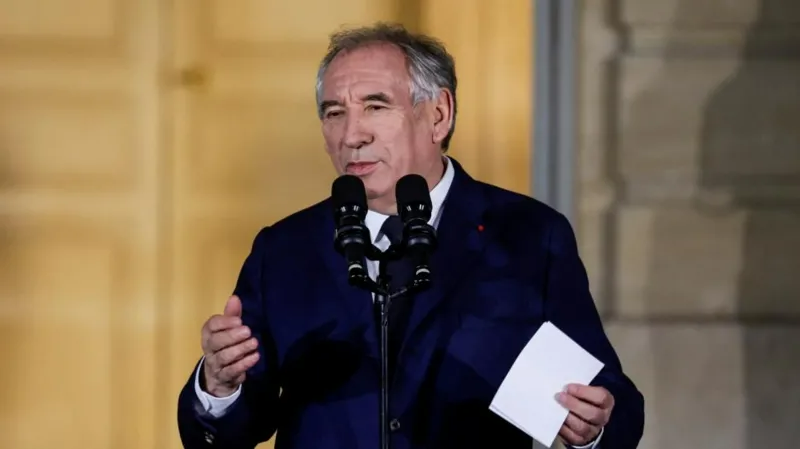

Centrist leader François Bayrou has become France’s latest prime minister, chosen by President Emmanuel Macron in a bid to end months of political turmoil.

Bayrou, a 73-year-old mayor from the south-west who leads the MoDem party, said he was fully aware of the “Himalayan” task facing France, and he vowed to “hide nothing, neglect nothing and leave nothing aside”.

He is seen by Macron’s entourage as a potential consensus candidate and his task will be to avoid the fate of his predecessor.

Ex-Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier was ousted by MPs nine days ago and welcomed Bayrou to the prime minister’s residence on Friday.

Barnier was voted out over a budget aimed at cutting France’s budget deficit, which is set to hit 6.1% of economic output (GDP) this year. Bayrou said the deficit and public debt were a moral as well as a financial problem – because “passing it on to one’s children is a terrible thing to do”.

Macron is half-way through his second term as president and Bayrou will be his fourth prime minister this year.

French politics has been deadlocked ever since Macron called snap parliamentary elections during the summer and an opinion poll for BFMTV on Thursday suggested 61% of French voters were worried by the political situation.

Although a succession of allies lined up to praise Bayrou’s appointment, Socialist regional leader Carole Delga said the whole process had become a “bad movie”. Far-left France Unbowed (LFI) leader Manuel Bompard complained of a “pathetic spectacle”.

The centre-left Socialists said they were ready to talk to Bayrou but would not take part in his government. Leader Olivier Faure said because Macron had chosen someone “from his own camp”, the Socialists would remain in opposition.

President Macron has vowed to remain in office until his second term ends in 2027, despite Barnier’s downfall last week.

He cut short a trip to Poland on Thursday and had been expected to name his new prime minister on Thursday night, but postponed his announcement until Friday.

He then met Bayrou at the Elysée Palace and a final decision was made hours later. But in an indication of the fraught nature of the talks, Le Monde newspaper suggested that Macron had preferred another ally, Roland Lescure, but changed his mind when Bayrou threatened to withdraw his party’s support.

Bayrou arrived at the prime minister’s residence at Hôtel Matignon late on Friday afternoon. A red carpet had been rolled out for the transfer of power even before his name was confirmed.

His challenge will be in forming a government that will not be brought down the way his predecessor’s was in the National Assembly. The far left France Unbowed (LFI) have already threatened to demand a vote of no confidence as soon as they can.

Ahead of his appointment, Macron held round-table talks with leaders from all the main political parties, bar the far left of Jean-Luc Mélenchon and far-right National Rally of Marine Le Pen.

The question is who can be persuaded to join Bayrou’s government, or at least agree a pact so they do not oust him.

When the only possible means of survival for a minority government is to build bridges on left and right, Bayrou has the advantage of having passable relations with both sides, reports BBC Paris correspondent Hugh Schofield.

Michel Barnier was appointed only in September and said on Friday he knew from the outset that his government’s days were numbered.

He was voted out when Le Pen’s National Rally joined left-wing MPs in rejecting his plans for €60bn (£50bn) in tax rises and spending cuts.

His outgoing government has put forward a bill to enable the provisions of the 2024 budget to continue into next year. But a replacement budget for 2025 will have to be approved once the next government takes office.

Bayrou said that reducing France’s deficit and debt was a “moral obligation”.

Barnier wished his successor his best wishes, adding that “our country is in an unprecedented and serious situation”.

Under the political system of France’s Fifth Republic, the president is elected for five years and names a prime minister whose choice of cabinet is then appointed by the president.

Unusually, President Macron called snap elections for parliament over the summer after poor results in the EU elections in June. The outcome left France in political stalemate, with three large political blocs made up of the left, centre and far right.

Eventually he chose Barnier to form a minority government reliant on Marine Le Pen’s National Rally for its survival. Macron is now hoping to restore stability without depending on her party.

Three centre-left parties – the Socialists, Greens and Communists – broke ranks with the more radical left LFI by taking part in talks with Macron.

However, they made clear they wanted a prime minister from the left, rather than a centrist.

“I told you I wanted someone from the left and the Greens and I think Mr Bayrou isn’t one or the other,” Greens leader Marine Tondelier told French TV on Thursday.

Patrick Kanner of the Socialists said that just because his party was not joining Bayrou’s government, “that doesn’t mean we’re going to bash it”.

Sébastien Chenu, a National Rally MP, said for his party it was less about who Macron picked than the “political line” he chose. If Bayrou wanted to tackle immigration and the cost of living crisis then he would “find an ally in us”.

Relations between the centre left and the radical LFI of Jean-Luc Mélenchon appear to have broken down over the three parties’ decision to pursue talks with President Macron.

After the LFI leader called on his former allies to steer clear of a coalition deal, Olivier Faure of the Socialists told French TV that “the more Mélenchon shouts the less he’s heard”.

Meanwhile, Marine Le Pen has called for her party’s policies on the cost of living to be taken into account by the incoming government, by building a budget that “doesn’t cross each party’s red lines”.

+ There are no comments

Add yours