China’s population has fallen for the first time in six decades, official statistics revealed earlier this week – but this trend may not spell doom for the country in the short term, experts say.

Beyond 2030, however, demographic stress will be a drag on growth in what is currently the world’s second-largest economy.

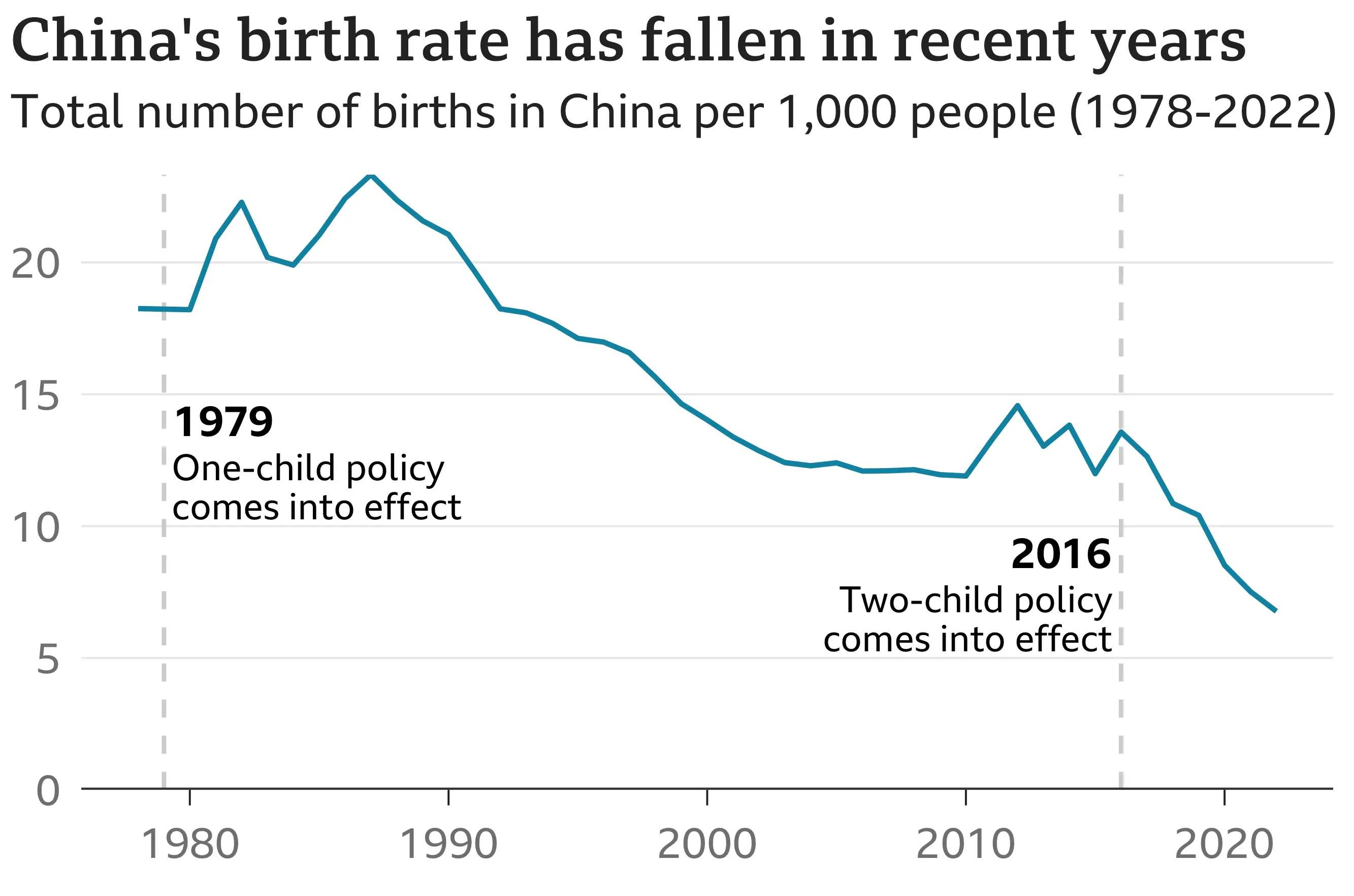

The number of Chinese people fell by 850,000 from the previous year to 1.4118 billion, the statistics showed. Its birth rate had been slowing for years, prompting a range of policies to try to slow this trend, including scrapping the country’s infamous one-child policy seven years ago.

But there are no easy fixes to this conundrum, economists and demographers say, given the unique trajectory in which the Chinese population has aged in recent years.

While ageing populations have posed a challenge to economies around the world, the greater concern for China is the rapid pace at which this has been unfolding in the midst of its middle-income transition.

In short, China is getting old before it gets rich.

Its statistics bureau said this week that its population had fallen for the first time in 60 years, with the birth rate also hitting a record low – to no surprise. Some researchers believe the population decline started in 2018 and census estimates have been inaccurate.

In any case, China’s working-age population has been on a slump since 2012. Its age-dependency ratio, which is the ratio of children and retired people to the working age population, has risen from 37.12% in 2010 to 44.14% in 2020.

Based on UN estimates, the number of Chinese aged between 15 and 64 will fall by more than 60% this century.

But Andrew Harris, deputy chief economist at Fathom Financial Consulting, said the country had a pool of cheap rural labour that could help fill manufacturing gaps in urban areas.

There is still “significant slack” in the manufacturing and construction sectors, Mr Harris added, noting that Fathom estimates that roughly one third of workers in the construction sector are underemployed, which means they are producing less than they potentially could.

“The broader demographic story won’t bite fully on China’s growth until both of these sources of slack have been exhausted,” he said.

According to Paul Cheung, Singapore’s former chief statistician, China has “plenty of manpower” and “a lot of lead time” to manage the demographic challenge.

“They are not in a doomsday scenario right away,” Prof Cheung said.

He also pointed to how countries like Japan and Singapore had managed to provide a safety net for their ageing citizenry while maintaining relative economic stability.

But not everyone is as sanguine.

“The major difference between China and countries like South Korea and Japan is that its demographic (stress is) biting at much lower levels of income,” Mr Harris said.

A 2019 report by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences predicted that the country’s main pension fund would be depleted by 2035, in part because of its shrinking workforce.

Studies by US think-tank Pew Research showed that some seven in 10 people in China already felt its public health system was under strain in 2016. A greying population and the spiralling Covid crisis have placed additional stresses on it.

China’s population decline could send ripple effects across the global economy.

For one, a shrinking workforce means rising labour costs, which could increase consumption and production costs. Recent reports have already shown China – long dubbed the “factory of the world” – losing manufacturing operations to other developing countries in Asia and South America.

“China’s shrinking labour force and manufacturing recession will lead to high prices and high inflation in the US and EU,” said Yi Fuxian, a researcher at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and longtime critic of China’s now-defunct one-child policy.

Given how its recent attempts to raise fertility rates have met with limited success, China may have to look at other ways to sustain growth.

This will involve making hard political decisions, said George Magnus, an independent economist and associate at the China Centre at Oxford University.

For instance, it should consider national legislation to raise retirement ages, Mr Magnus said. The current retirement age for most men in China is 60, while the OECD average is 64.2. The number stands at 55 for female civil servants and 50 for female blue-collar workers.

However, previous calls to raise the retirement age have sparked backlash in China, with older workers not wanting to delay access to their pensions.

China is already pursuing automation through robotics and artificial intelligence, but the impact on productivity is still unclear, Mr Harris said.

Another solution would be to bolster the population through immigration, although this is not an option that the Chinese Communist Party has favoured historically, he noted.

Although China can no longer rely on its demographic dividend to fuel its economy, that may not be a bad thing if it manages to seek growth from other sources such as productivity, some observers say.

“We should be much more nuanced about the stall in China’s population growth. Planetary sustainability and urban congestion are better served by a more stable world population, which may entail declines in some countries,” Mr Magnus said.

“Demography is not destiny. The key is to get these and other nations to focus like a laser beam on ‘coping mechanisms’.”

+ There are no comments

Add yours